Newnans Lake Kayak (& Canoe) tours

Newnans Lake Kayak (& Canoe) tours

Group size: 1 – 24 people

Trip length: 3 – 4 hours

Skill level: Beginner

Difficulty: The shallow water may require an occasional scooch or pry, but you shouldn’t have to get out of your boat.

Once we’ve passed the initial shallow area, the rest of the trip has plenty of water. Winds

can be brisk on the open lake, but the tall marsh vegetation should give good protection.

Cost

Most guided tours are $50 per person. (includes boat, paddle, vest, shuttling and your guide)

Using your Own Boat – $40. (many paddlers with their own boats like to join us to learn more about the history, archaeology and natural history of these rivers).

Dates

Join a scheduled tour (see tour calendar ), or suggest one. Find a free date on the calendar and suggest the trip of your choice. If there are no conflicts, we’ll post it!

OR

Schedule a private tour. Use contact form, email us at riverguide2000@yahoo.com or call (386-454-0611)

Location

Check the River Locator Map or Click the link below for a local map and then use zoom and panning arrows to explore the area. (Note: the marker is NOT our meeting place, but a nearby landmark.

Local MapDescription

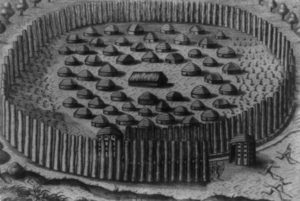

Located only a few miles northeast of Paynes Prairie, this lake shares much of the amazing cultural and natural history of the famous prairie. The archaeological record shows that this area was a favorite hunting ground for the first nomadic paleo-Indians and later, was the site of several important settlements as then Indian cultures became more complex and stationary. Running along the lake’s eastern shore, one of Florida’s most important trade routes, known as the “Alachua Trail” connected the Paynes Prairie region to central Georgia. For thousands of years, much of the commerce, migrations and movements of armies, both Indian and white, into north Florida, came along this route. The road through Windsor is one of the few segments of this ancient highway that is still in use.

In the 20th century, the shallow lake became nationally famous for the abundance and size of it’s large-mouth bass. The unofficial record for a large-mouth bass (recorded by a fish market before records were ke pt), was caught on Prairie Creek, the lake’s natural outlet which carries it’s waters to Paynes Prairie and River Styx. Today, the combination of excessive nutrients and drought conditions have put Newnan’s reputation on hold, but there is little doubt the lake, with all it’s abundance will return – but when?

pt), was caught on Prairie Creek, the lake’s natural outlet which carries it’s waters to Paynes Prairie and River Styx. Today, the combination of excessive nutrients and drought conditions have put Newnan’s reputation on hold, but there is little doubt the lake, with all it’s abundance will return – but when?

Wildlife

Newnans Lake has long been known as a bird watchers paradise. With the current (winter of 2001 – ’02) presence of a huge marshland at the lakes perimeter, the birds are more numerous than ever. In fact, some birds are seen in such numbers as to warrant a rare opportunity to use collective nouns (they’re too fun to ignore). So…

In the trees at lake’s edge, we often see a gulp of cormorants, whose deep, guttural croakings sound like Geiger counters, intensifying quickly when limb-side neighbors encroach on each others 1 foot perimeter of ‘personal space.’ A murder of crows (not to be confused with an unkindness of ravens) is less likely, but possible. Occasionally, a siege of great blue herons will be seen in the shallows, also mindful of each other’s personal space issues.

Hidden in the marshes, you might come on a sord of mallards or a spring of teal. While out in the open water, you’re more likely to see a cover of coots, or a paddling of ducks (if they take flight, the paddling becomes a brace). Overhead, it’s doubtful you’ll see a convocation of bald eagles or a kettle of hawks, but you’ll probably see one or two.

Hidden in the marshes, you might come on a sord of mallards or a spring of teal. While out in the open water, you’re more likely to see a cover of coots, or a paddling of ducks (if they take flight, the paddling becomes a brace). Overhead, it’s doubtful you’ll see a convocation of bald eagles or a kettle of hawks, but you’ll probably see one or two.

Sadly, I doubt anyone will spot a bouquet of pheasants (they don’t live here) or an ostentation of peacocks (they don’t live here either, though we often see an introduced population on an isolated island during our Crystal River trips). And, if you get tired, you need only look to the ever-present wake of vultures circling overhead for inspiration to make it back to the launch site.

Newnan’s Lake is also a well known haunt for alligators. Try not to wind up with a boatload.

History

Some of this amazing lake’s history is only recently coming to light. During the last 2 years of extreme drought, nearly 100 ancient Indian canoes have been found on the exposed lake bed. This is more than all previous finds in Florida combined. Fifty four of the canoes were studied in detail, and then reburied on site. Of these 54, almost all were made of pine logs. Only two were of cypress. Their ages range from about 3,000 B.C to about A.D. 500. Along with the canoes, archaeologists discovered stone tools, projectile points, pottery shards and a 260 year old paddle (one of only 15 ever found in the state).

The Paynes Prairie region, which includes this lake as well as Orange and Lochloosa Lakes and Levy, Ledwith and Paynes Prairies, are rich in archaeological sites. Near the southern shores of Newnan’s, several large village sites have been excavated, including the type locality for a kind of spear point known as the “Newnans point.”

Timucua Indians referred to this lake as Amaca. But special interest has been drawn by the later-arriving Seminoles name for the lake Pithlachocco. The name’s meaning, “place where boats are made,” has taken on new significance with the canoe discoveries. The current name can also be credited to the Seminoles who, in 1812, thrashed a troop of Georgia militia under the leadership of Colonel Daniel Newnan. For over a week, the Seminoles under King Payne (for whom the famous prairie nearby was named) kept the Georgians under siege in a little, makeshift breastwork, (sometime generously  referred to as a “fort” Newnan). Finally, in desperation, the soldiers were able to escape under cover of darkness. I can’t help but wonder if the lake’s current name started as something like “the lake where Newnan got his butt whipped,” only to evolve into the trimmed down version we know today.

referred to as a “fort” Newnan). Finally, in desperation, the soldiers were able to escape under cover of darkness. I can’t help but wonder if the lake’s current name started as something like “the lake where Newnan got his butt whipped,” only to evolve into the trimmed down version we know today.

For those who are interested in Florida’s history, here’s a story (editorial) I wrote for the Gainesville Sun early in 2000. It was written as a “tongue-in-cheek” response to the suggestion by some Gainesville residents that Newnan’s Lake’s name be changed back to it’s Indian name, Pithlachocco.

It was the early 1800’s and a small army of American volunteers, some from Tennessee and Georgia, launched a raid to capture lands that didn’t belong to them. The plan went awry when they encountered a force much larger than their own, forcing them to “dig-in” where they were and make a stand. For many days they remained under siege and, when it was over, the original landowners emerged victorious and were still in possession of their land. Some might say the white “intruders” got what they deserved. But, I don’t believe I’ve ever heard one bad thing said about the men who fought and died in the Alamo.

Now, I’m not suggesting that Daniel Newnan be compared to Davey Crockett (though the facts might warrant it), I just think that before we continue the thrashing of Daniel Newnan which was begun by King Payne’s Seminoles two centuries ago, we had better take a moment to reflect on the precedent it would set. If we decide to change the name of Newnan’s lake on the basis that it’s namesake abused the Indians, we’re opening a fairly large and ugly can of worms.

Immediately, we’d have to contend with names like Columbus, De Leon and De Soto. And these are just the characters from the opening pages of our nation’s family album. The fact is, this country was founded on deeds such as Newnan’s raid. But, rather than go through our whole dirty laundry list, I’ll limit myself to a single tale. And, as long as we’ve breached the subject of the Alamo, let’s start there.

It’s February, 1836. With the situation looking desperate in Texas, the President of the United States ordered the Major General in command of the Army’s Western Division to go to Texas. His orders – to assist in the efforts to take a part of Mexico (Texas) away from it’s lawful owners. When the General received his orders he was at Tampa Bay, gearing up for an attack on the Seminoles (led by King Payne’s nephew, Micanopy). Rather than follow his orders to head for Texas, the General decided to disobey them and proceeded with his initial plans to march into Florida.

On February 28, our hero’s force came under fire from the Seminoles, and, like Newnan, was forced to quickly build a makeshift breastwork of logs. Here, also like Newnan, he was kept under siege for over a week. By an odd coincidence, during the same 8 days that our hero’s troop was under siege on the banks of the Withlacoochee River, the men he was supposed to be aiding in Texas were also being kept under siege in a small church in San Antonio called the Alamo. Who knows how the story would have ended if the General had followed orders. As it was, the 189 men in the Alamo were all killed, while those in Florida were finally rescued by reinforcements.

So, who was this “hero” who launched an assault to evict the Seminoles from their homeland? General Edmund P. Gaines (see – massacre of “Negro Fort”), the namesake of our fair community And, who was the U.S. president at the helm of both operations, Texas and Florida? Andrew Jackson, a self-proclaimed Indian hater of the worst kind (see – Battle of Horseshoe Bend), for whom our neighbors named their city.

My purpose here is not to disparage the actions of Gaines, Jackson or even Newnan. I just think they need to be kept in context of the times. Nor am I saying that changing Newnan’s Lake’s name is a bad idea. I personally like the idea and prefer the Indian names – especially when they are as fitting as Pithlachocco (“place where they make boats”). I’m just concerned that if we start changing the names of places just because their namesake’s deeds don’t stand up to today’s P.C. standards, we might soon be turning to the sports section of the Hogtown Sun to get scores for the Cowford Jaguars football team.